Introduction

The most profound breakthroughs in human history share a singular trait: they are obvious in retrospect but remained “unsolvable” for decades prior to their arrival. We recognize a smartphone, a reusable rocket, or an mRNA vaccine as “working” the moment we see them, yet the path to their discovery remained hidden behind a wall of infeasibility.

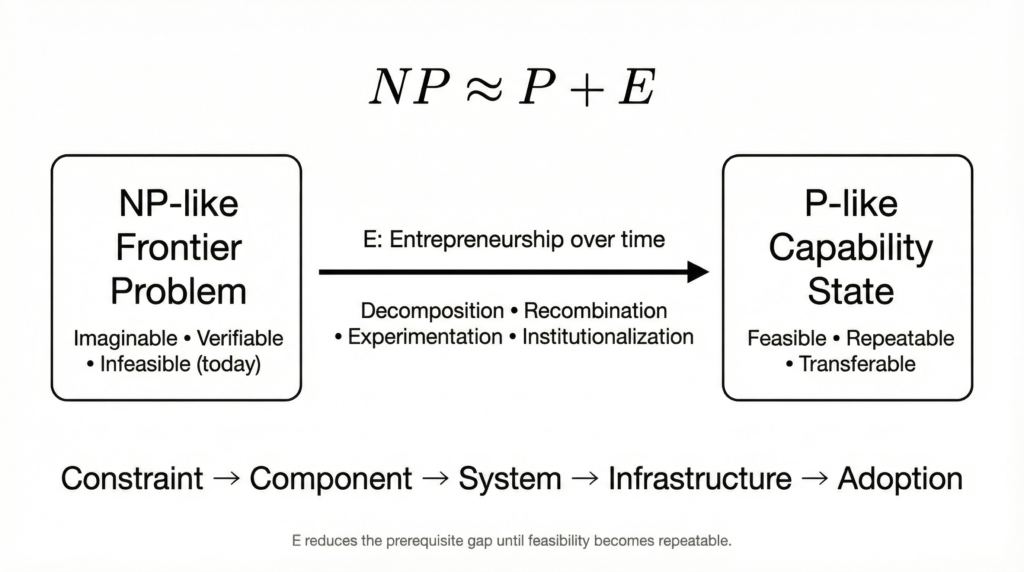

In computer science, this asymmetry defines the 𝑃 vs 𝑁𝑃 problem. It asks whether every problem whose solution can be verified quickly (𝑁𝑃) can also be solved quickly (𝑃). While the mathematical proof remains a Millennium Prize mystery, the world of venture building operates on a settled practical reality: Verification is easy; discovery is hard.

We define this “Verification Gap” as the primary frontier of human progress. A problem exists in an 𝑁𝑃-like state when the outcome is imaginable and verifiable, but the search space is too vast or the constraints too heavy for current systems to navigate.

To bridge this gap, we must introduce the catalyst of progress:

![]()

where 𝐸 (Entrepreneurship) is the compounding process of decomposition, recombination, experimentation, and institutionalization that collapses frontier complexity into repeatable capabilities.

From 𝑃 vs 𝑁𝑃 to Progress

In 1971, Stephen Cook formalized the structure of “hard” problems. His work on 𝑁𝑃-completeness revealed a recurring pattern in the universe: many outcomes are trivial to verify once they exist, yet remain nearly impossible to discover from scratch.

In the language of computational complexity, this is captured by two distinct classes:

- 𝑃 (Polynomial Time): Problems that are predictable and solvable efficiently. These are the “knowns” of industry-standard manufacturing, logistics, and established protocols.

- 𝑁𝑃 (Nondeterministic Polynomial Time): Problems where a proposed solution is easy to verify, but finding it is hard. Think of discovering a specific molecular compound: once you have the drug, testing its efficacy is a 𝑃-like task. Finding that specific molecule in a near-infinite search space is an 𝑁𝑃-like challenge.

The central mystery of computer science is whether these classes are actually the same (𝑃 = 𝑁𝑃). While unproven, the working assumption of the modern world is 𝑃 ≠ 𝑁𝑃: verification is fundamentally easier than discovery.

This same asymmetry governs the arc of progress. Once a breakthrough exists, its validity is self-evident; before it exists, feasibility is blocked by an incomplete “prerequisite stack.” In this framework, “Unsolvable” is merely shorthand for a missing component, an unproven method, or an absent institutional permission.

Consequently, the most important question for a strategist is not “Who had the idea first?” but rather:

What specific chain of reductions finally made this outcome feasible?

This is where entrepreneurship enters. It is not merely the act of “running a business,” but the human mechanism that decomposes constraints, invents enabling components, and incrementally converts frontier problems into solvable states.

The Contribution: 𝑁𝑃 ≈ 𝑃+𝐸

The 𝑃 ≠ 𝑁𝑃 asymmetry provides more than a computational metaphor; it offers a foundational framing for economic feasibility. By introducing entrepreneurship as a variable, we move from a static problem to a dynamic path of reduction.

This relationship defines the Solvability Gradient—the process through which feasibility emerges across time:

𝑁𝑃 (The Frontier): A problem space that is imaginable and verifiable in principle, yet infeasible in practice due to a missing prerequisite stack.

𝑃 (The Capability): A state of solved complexity where the outcome is feasible, repeatable, and transferable because the enabling prerequisites finally exist.

𝐸 (The Operator): The compounding force of entrepreneurship that collapses the prerequisite gap through the systematic creation, recombination, and testing of capabilities.

![]()

Entrepreneurship is a reduction engine. It does not simply “create value”; it shrinks the distance between the “unsolvable” and the “solvable” by engineering the next feasible step.

𝐸 Mechanism: What “𝐸” Actually Does

A frontier problem (𝑁𝑃-like) collapses into a capability state (𝑃-like) when the entrepreneurial operator successfully resolves the prerequisite stack. In practice, “unsolvable” is rarely a statement of impossibility; it is a diagnostic of incompleteness.

To move a problem from the frontier into the stack of infrastructure, the prerequisite gaps—the technical and institutional debt—must be identified and cleared. These typically include:

- Critical Components: The absence of a viable energy source, material substrate, or base technology.

- Workable Architecture: The lack of a blueprint for how disparate parts integrate into a functional whole.

- Method of Control: Insufficient stability, safety protocols, or operational precision.

- Means of Measurement: The inability to test, verify, or iterate with high fidelity.

- Enabling Infrastructure: The lack of manufacturing scale, logistics, standards, or regulatory permissions.

Entrepreneurship is not a function of “hustle”; it is a function of Complexity Reduction. 𝐸 employs four specific mechanics to transition a problem into the infrastructure stack:

- Decomposition (Isolating the Bottleneck):

The entrepreneur does not solve “a problem”; they solve the specific constraint that makes the problem 𝑁𝑃-hard. By breaking a grand vision into discrete, verifiable sub-problems, 𝐸 identifies which segments of the stack are already 𝑃 (solvable) and which require targeted invention. - Recombination (Architectural Innovation):

Most breakthroughs are not the result of new atoms, but new arrangements. Entrepreneurship is the act of “compiling” existing components—often from disparate industries—into a new system. It is the realization that a problem remains unsolvable only because the necessary parts have not yet been networked together. - Experimentation (Search Space Reduction):

If the path to a solution is unknown, the search space is infinite. 𝐸 acts as a filter, using iterative, low-cost cycles to “kill” unproductive paths. This turns a high-entropy search into a lookup table. We do not find the answer; we eliminate the non-answers until the solution is the only thing remaining. - Institutionalization (Hardening into Infrastructure):

The final act of 𝐸 is to remove the need for entrepreneurship. By establishing standards, manufacturing protocols, and regulatory pathways, the “innovation” is hardened into infrastructure. At this point, the 𝑁𝑃 problem is fully reduced to 𝑃: it is no longer a discovery; it is a utility.

Validation: The mRNA Stack

The development of mRNA technology is the definitive arc of complexity reduction. The end-state was always verifiable: either a cell can be reliably instructed to produce a target protein safely, or it cannot. For decades, the concept was clear, yet the capability remained effectively “unsolvable” because the prerequisite stack was incomplete.

Feasibility emerged through a sixty-year chain of sequential reductions:

- (1961) The Conceptual Frontier (Decomposition): Messenger RNA is identified as the transient information carrier. The problem shifts from “unknown” to “imaginable.” We realize biology has a software layer.

- (1990) The Feasibility Signal (Experimentation): Researchers demonstrate that direct injection of RNA can drive protein expression in vivo. This proves “biological execution” is possible, though the system remains too unstable for clinical use.

- (2005) The Tolerance Barrier (Constraint Reduction): The Karikó-Weissman breakthrough. By modifying nucleosides (pseudouridine), researchers “cloak” the mRNA from the body’s innate immune recognition. This reduces the primary 𝑁𝑃 variable—toxicity—into a manageable parameter.

- (2010s) The Delivery Stack (Recombination): Lipid nanoparticle (LNP) systems mature. Innovation here is the recombination of nanotechnology and molecular biology to protect the code until it reaches its destination.

- (2020–2021) The Institutional Gate (Institutionalization): Emergency Authorizations (Dec 2020) followed by full FDA approval (Aug 2021) validate the platform at a population scale. Standards, manufacturing protocols, and regulatory pathways are finalized.

In this arc, 𝐸 is visible as the systematic clearing of technical debt. By decomposing immune activation, recombining delivery systems, and institutionalizing manufacturing, the 𝑁𝑃-like frontier problem collapsed into a 𝑃-like capability state: achievable, repeatable, and globally transferable.

Complexity is a wall; Entrepreneurship is the engineering of the door.

Dr. Ali

Checklist for Breakthrough Strategy

To apply the 𝑁𝑃 ≈ 𝑃 + 𝐸 lens to breakthrough spaces, use these four diagnostic variables to audit your trajectory:

- Identify the Binding Constraint: Determine what is specifically “unsolvable”. Isolate whether the fundamental block lies in energy, materials, control, cost, safety, production, or regulation.

- The Verification State: Define what a minimal demonstration of the real capability looks like. If you cannot prove the solution, you cannot engineer the path to it.

- Locate the Enabling Invention: Identify the single component, method, or design shift required to reduce the immediate gap. Solve for the next step of feasibility.

- Architectural Recombination: Determine which existing technologies can be rearranged into a new architecture to shrink the search space. Breakthroughs are often new configurations of old components.

The Infrastructure of Discovery

Ecosystems do not produce breakthroughs by having better ideas; they produce them by lowering the cost of complexity reduction. In high-performance environments, entrepreneurship compounds because the prerequisite stack is standardized and accessible.

Common Reduction Accelerators include:

- Prototyping Infrastructure: Shared labs and facilities that turn high-cost experiments into standard procedures.

- Measurement Regimes: Universal standards that ensure progress is comparable and transferable across the network.

- Epistemic Density: Dense networks that facilitate knowledge spillovers and rapid talent mobility.

- Institutional Trust: Credible IP regimes and procurement pathways that provide the “institutional permission” required for scale.

- Iterative Tolerance: Cultural and economic environments that allow for experimentation without catastrophic penalty.

In these environments, entrepreneurship reduces frontier problems at an accelerated rate because the components of the solution can be built, shared, and recombined with maximum efficiency.

Conclusion

Entrepreneurship is the force that moves the feasibility frontier. “Unsolvable” problems are rarely solved by a single heroic leap; they collapse when entrepreneurial effort decomposes them into constraints, builds enabling components, and tests reality until feasibility stabilizes.

The wheel reduced a mobility constraint; the engine reduced a power constraint. Every successful reduction makes the next solution easier to find. This is ![]() in action: the compounding reduction of complexity that turns impossibility into capability.

in action: the compounding reduction of complexity that turns impossibility into capability.

We have long treated entrepreneurship as a function of capital or grit. It is neither. It is a function of complexity reduction. When you decompose the frontier, you are not just building a company; you are solving a fundamental equation of human progress. You are the bridge that turns the imaginable into the inevitable.

Acknowledgments

References & Further Readings

- Aaronson, S. (2011). Why philosophers should care about computational complexity. Computational Complexity, 20(1), 57–59.

- Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organization Science, 22(5), 1123–1137.

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

- Baron, R. A. (2006). Opportunity recognition as pattern recognition: How entrepreneurs “connect the dots” to identify new business opportunities. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(1), 104–119.

- Bontis, N., et al. (2021). Mathematical Modeling of Intellectual Capital and Business Efficiency of Small and Medium Enterprises. Mathematics, 9(18), 2305.

- Brenner, S., Jacob, F., & Meselson, M. (1961). An Unstable Intermediate Carrying Information from Genes to Ribosomes for Protein Synthesis. Nature, 190(4776), 576–581.

- Byers, T. H. (2011). Technology ventures from idea to enterprise. McGraw-Hill.

- Chopra, K. N. (2015). Mathematical Modeling on “Entrepreneurship Outperforming Innovation” for Efficient Performance of the Industry. AIMA Journal of Management & Research, 9(3/4), 1-9.

- Cook, S. A. (1971). The complexity of theorem-proving procedures. Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (pp. 151–158).

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10–11), 1105–1121.

- Gilbert, N., & Ahrweiler, P. (2013). Agent-based modeling for entrepreneurship research: Opportunities and challenges. Emerald Insight.

- Gordijn, J., & Akkermans, H. (2015). Business model analysis using computational modeling: A strategy tool for exploration and decision-making. ResearchGate.

- Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R., & Dong, Y. (2021). Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nature Reviews Materials, 6(12), 1078–1094.

- Karikó, K., et al. (2005). Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA. Immunity, 23(2), 165–175.

- Karp, R. M. (1972). Reducibility among combinatorial problems. Complexity of Computer Computations (pp. 85–103). Springer.

- Keyhani, M., Lévesque, M., & Madhok, A. (2019). Computational modeling of entrepreneurship grounded in Austrian economics: Insights for strategic entrepreneurship and the opportunity debate. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105886.

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty, and profit. Houghton Mifflin.

- Lee, J. (2013). Mathematical modeling and quantitative analysis of entrepreneurship. Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management.

- Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations: A synthesis of the research. Prentice Hall.

- Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity: A guided tour. Oxford University Press.

- Pardi, N., Hogan, M. J., Porter, F. W., & Weissman, D. (2018). mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17(4), 261–279.

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Free Press.

- Ries, E. (2011). The Lean Startup: How constant innovation creates radically successful businesses. Crown Publishing Group.

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243–263.

- Sarkar, D., et al. (2024). Analyzing the nexus between entrepreneurship and business mathematics – a comprehensive study on strategic decision-making, financial modeling, and risk assessment in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). International Journal of Research and Review, 11(2), 41-53.

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy. Harper & Brothers.

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

- Wolff, J. A., et al. (1990). Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science, 247(4949), 1465–1468.